This study dives deep into the potential of cutting-edge facial analysis and wearable monitoring technologies to revolutionize anxiety and depression screening in medical students. By comparing the accuracy, feasibility, and acceptability of these novel tools to gold-standard diagnostic questionnaires, we aim to lay the groundwork for more objective, efficient, and scalable mental health assessment that could enable earlier detection and life-changing intervention for struggling students. Rigorous methodology and a steadfast commitment to participant wellbeing and data ethics are at the heart of this groundbreaking investigation.

Imagine for a moment that you’re a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed medical student. You’ve poured your heart and soul into making it this far, sacrificing countless hours of sleep and socializing to master the intricacies of the human body and the art of healing. But beneath the crisp white coat and confident exterior, a storm is brewing.

You see, the very nature of medical education—with its high-stakes exams, grueling clinical rotations, and pressure to absorb vast amounts of ever-evolving knowledge—is a perfect recipe for stress. And all too often, that stress can simmer and swell into more insidious mental health struggles like anxiety and depression.

In fact, study after study has shown that medical students suffer from these conditions at alarmingly high rates compared to their non-medical peers. One meta-analysis found that 27.2% of medical students screened positive for depression—that’s more than 1 in 4 future doctors! And for anxiety, estimates range from 7% to a staggering 44.7% across different studies.

But here’s the kicker: despite the prevalence of these mental health challenges, they often go unrecognized and untreated. The rigorous curriculum leaves little time for self-care, and the competitive culture can make students reluctant to admit they’re struggling for fear of being seen as weak or unfit for the profession.

As a result, many suffer in silence, grinning and bearing it until they reach a breaking point. And that’s not just a personal tragedy—it’s a public health crisis waiting to happen. After all, how can we expect our healers to provide top-notch care if they’re drowning in unaddressed distress?

Now, it’s not that we’re totally in the dark about medical students’ mental health. Many schools do make an effort to screen for anxiety and depression, usually by having students fill out self-report questionnaires. These include well-validated measures like the PHQ-9 for depression and the GAD-7 for anxiety, which ask students to rate how often they’ve experienced various symptoms over the past few weeks.

And don’t get me wrong, these questionnaires are a crucial first step. They’re relatively quick, cheap, and easy to administer, and they provide a standardized way to flag students who may be struggling. But they also have some glaring limitations.

For one, they rely on students being honest and insightful about their own mental state. But let’s face it, admitting you’re anxious or depressed can be tough, especially in a high-pressure environment where everyone seems to have it together. There’s a strong stigma around mental illness in medicine, and students may downplay their symptoms for fear of being labeled as weak or incompetent.

What’s more, some students may not even recognize that what they’re feeling is a problem. They may chalk it up to the “normal” stress of med school or assume everyone feels this way. And if they’ve been powering through for a while, they may have gotten so used to operating at a baseline level of distress that they don’t realize how much it’s impacting them.

There’s also the issue of timing. Most schools only screen once or twice a year, if that. But mental health is dynamic, and a student who seems fine in September may be drowning by December. Relying on sporadic check-ins means we’re likely missing a lot of students who are struggling in the interim.

So what’s the solution? How can we catch more students who are slipping through the cracks and connect them with support before they hit rock bottom? Enter the brave new world of digital phenotyping.

This buzzy term refers to the idea of using data from smartphones, wearables, and other digital devices to infer mental states and behaviors. The basic premise is that our technology use leaves behind a trail of “digital breadcrumbs” that, when analyzed in aggregate, can paint a surprisingly rich picture of our psychological wellbeing.

For example, research has found that changes in typing speed, voice tone, and even the emoji we use can all be subtle signs of shifting mood. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. With the explosion of AI and machine learning, we now have the power to crunch vast amounts of behavioral data and spot patterns that the human eye would never catch.

Now, applying this approach to medical student mental health is still a young field, but a few tantalizing studies have hinted at its potential. For instance, one team found that an AI algorithm analyzing facial expressions and voice data could detect signs of anxiety and depression with over 90% accuracy! Another used smartwatches to track students’ sleep, physical activity, and heart rate, and found that certain patterns strongly predicted mental health symptoms.

Of course, this isn’t to say that technology should replace human judgment. We’re not quite at the point of having a robot therapist in every med school (though never say never!). But what if we could use these digital tools to supplement and enhance our current screening efforts? To flag students who might be flying under the radar and prompt a human check-in?

That’s where our study comes in. We’ve cherry-picked two of the most promising technologies out there—a cutting-edge facial analysis system and a top-of-the-line wearable monitor—and we’re putting them to the test in the ultimate real-world laboratory: medical school.

By comparing these gizmos to the tried-and-true questionnaires, we’re hoping to get a clear-eyed look at their accuracy, feasibility, and acceptability for detecting anxiety and depression. In other words, do they actually work? Can schools realistically implement them? And most importantly, will students be on board?

Because let’s not forget, for any screening tool to make a meaningful difference, it has to be something students will actually use. No matter how whiz-bang the technology, if it feels intrusive, impersonal, or just plain creepy, it’s DOA.

So buckle up, because we’re about to take a deep dive into the nitty-gritty of our study design. It’s not going to be a cakewalk—pioneering research never is. But if we get this right, the payoff could be huge: a future where no medical student has to suffer in silence, where mental health is monitored as routinely as physical health, and where we catch struggling students long before they reach a crisis point.

It’s an ambitious goal, but one that’s well worth fighting for. Because at the end of the day, our future doctors deserve better. They deserve a system that sees them, hears them, and supports them as whole people, not just walking encyclopedias of medical knowledge. And if a few strategically deployed robots can help us get there, then I say bring on the bots!

Alright, now that we’ve got the lay of the land, let’s get down to brass tacks. What exactly are we hoping to accomplish with this study? In a nutshell, we’ve got three key objectives, each building on the last to paint a comprehensive picture of these technologies’ potential:

Diagnostic Accuracy: First and foremost, we need to verify if these devices—the FACS system from DYAGNOSYS and the CardioWatch 287 bracelet from CORSANO—can accurately detect anxiety and depression in medical students compared to validated questionnaires.

We’ll be evaluating the FACS and CardioWatch against the gold-standard questionnaires (PHQ-9 and GAD-7). Specifically, we aim to determine:

Additionally, we seek to determine if these technologies can assess the severity of anxiety and depression, differentiate between mild, moderate, and severe cases, and track changes over time.

Feasibility: Assess whether the FACS system and CardioWatch 287 can be seamlessly integrated into clinical settings. This includes evaluating:

Acceptability: Evaluate the willingness of medical students to engage with these technologies. This encompasses:

By triangulating these three dimensions—accuracy, feasibility, and acceptability—we’ll be able to make an informed judgment about whether these technologies are ready for primetime in the medical education arena. And if they are, we’ll have a roadmap for how to implement them in a way that maximizes benefit and minimizes burden.

Alright, now that we’ve got our objectives straight, it’s time to get into the weeds of how we’re actually going to run this study. Buckle up, because we’re about to go on a wild ride through the wonderful world of research methodology!

At its core, this is a prospective, multi-center, cross-sectional diagnostic accuracy study. Let’s unpack that mouthful of jargon:

In essence, we’ll be putting the FACS and CardioWatch through a rigorous, real-world stress test to see if they can hold their own against the tried-and-true screening methods. It’s like a diagnostic decathlon, if you will.

But before we get to the fun gadgets, we need to talk about the most important piece of the puzzle: the participants. Who are we going to be testing these technologies on, and how are we going to find them?

The goal is to obtain a representative sample of medical students while minimizing any confounding factors that could skew the results. We want to test the technologies on real, diverse students, but we also need to ensure we’re comparing apples to apples, you know?

So how are we going to get these busy, stressed-out med students to take time out of their packed schedules to be poked, prodded, and analyzed? With a little creativity and a lot of incentives!

First, we’ll plaster eye-catching flyers all over campus with a catchy slogan like “Be a Mental Health Hero!” or “Get Paid to Fight the Stigma!”. We’ll also send out mass emails to the student listservs and post on social media, emphasizing how this study could help future generations of medical students.

But the real kicker will be the compensation. We’ll offer each participant a $50 gift card for their time and effort, plus a chance to win a brand-new iPad in a raffle at the end of the study. Because let’s face it, med students are more likely to show up for cold hard cash and shiny tech than for the warm fuzzy feeling of advancing science (though that’s a nice bonus).

We’ll also work closely with the school administration to make sure the study is well-integrated into the curriculum. Maybe we can offer extra credit for participating or schedule the sessions during designated “wellness” time. The key is to make it as easy and appealing as possible for students to say yes.

Of course, we’ll be sure to emphasize that participation is 100% voluntary and will have no bearing on their academic standing. We’ll also make it crystal clear that all data will be kept strictly confidential and used only for research purposes. Trust and transparency are essential when you’re asking people to bare their souls (and their sweat glands) for science.

The sample size was calculated using the OpenEpi® program version 3.01, utilizing the following equation:

[ n = \frac{DEFF \times N \times p(1-p)}{(d^2 \times Z_{1-\alpha/2}^2 \times (N-1) + p(1-p))} ]

Where:

Given these parameters, the OpenEpi® program calculated a sample size of 240 medical students to be surveyed.

To ensure robust assessment, we’ll employ several validated questionnaires:

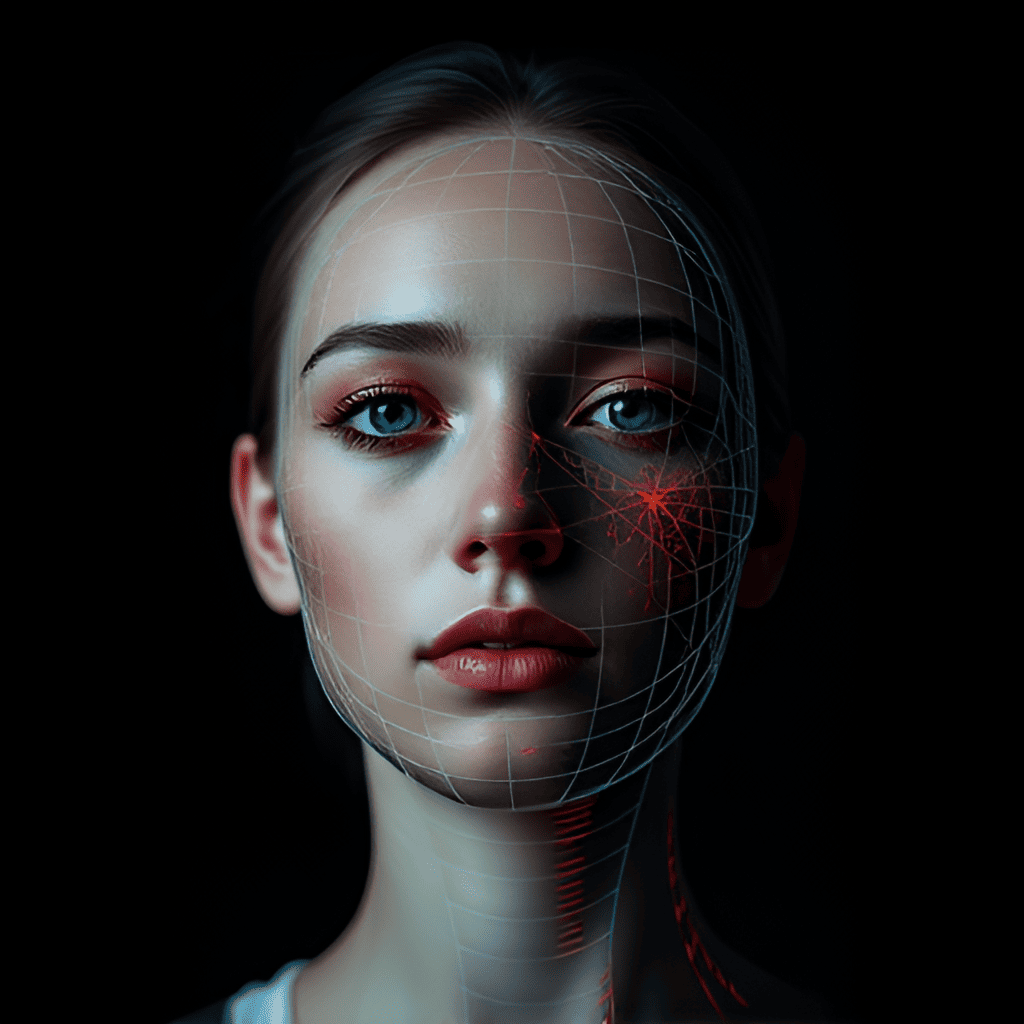

The FACS (Facial Action Coding System) system developed by DYAGNOSYS is designed to analyze facial expressions from video recordings to assess emotional states related to stress, anxiety, and depression. It utilizes the Facial Action Coding System to quantify specific facial muscle movements, known as Action Units (AUs), associated with these emotional states.

Video Input and Processing: The software accepts video files, capturing facial expressions over time. It processes each frame to detect faces using computer vision techniques, standardizing facial images by adjusting for lighting and orientation.

Prediction of Action Units: The system examines facial landmarks (e.g., eyebrows, eyes, mouth) to identify subtle muscle movements, quantifying the intensity of specific AUs linked to stress, anxiety, and depression.

Facial Action Coding System (FACS): FACS categorizes facial movements based on muscle activity. Each AU corresponds to specific facial muscles (e.g., AU4 is the “Eyebrow Lowerer”). Certain AUs are empirically linked to emotional states, enabling objective assessment.

Processed Board Display: Displays a processed image of the video (typically the last frame analyzed) with markers highlighting key facial features or analyzed muscle movements.

Emotional State Scores: Graphical representations show scores for stress, anxiety, and depression, standardized from 0 to 1, indicating the intensity of each emotional state.

Intensities of Action Units: A second graph displays the average intensities of each relevant AU, labeled with their number and brief descriptions for clarity.

Provides a non-invasive method to assess emotional states without relying on self-reporting, which can be influenced by stigma or reluctance. Useful in settings requiring continuous emotional assessment, such as therapy sessions or stress tests, and assists in diagnosing emotional disorders and monitoring treatment progress.

The CORSANO CardioWatch Bracelet 287 is utilized to monitor vital signs continuously during the administration of questionnaires and to capture data for the FACS system.

Widely used for continuous monitoring in both inpatient and outpatient settings, particularly in cardiology and oncology, providing detailed and accurate views of key physiological parameters.

Alright, now for the moment you’ve all been waiting for: the actual data collection! This is where the magic happens, where we put the FACS and CardioWatch to the test.

Initial Screening: Participants will complete the validated questionnaires (PHQ-9, GAD-7, BDI, and HAM-D) to establish baseline levels of anxiety and depression.

Device Deployment:

Data Synchronization: Data from both devices will be synchronized with the questionnaire results to enable comparative analysis.

Follow-Up: Participants diagnosed with anxiety or depression through questionnaires will be referred to UNIVÉRTIX’s psychology clinic for further support. However, the results from the test devices will not influence their diagnosis.

After administering the standard questionnaires to assess anxiety and depression, the sample will be divided into two groups for analysis:

The data from these groups will be cross-referenced with the data obtained from the FACS system and the CardioWatch bracelet to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the devices.

The FACS (DYAGNOSYS) and CardioWatch 287 (CORSANO) are expected to demonstrate a strong correlation with the validated questionnaires used as benchmarks for diagnosing depression and anxiety. Specifically, we anticipate:

Overall, the study aims to validate the effectiveness of these technologies in providing a more robust and efficient approach to assessing mental disorders, potentially offering a scalable solution for medical schools worldwide.

All collected data will be stored in the DYAGNOSYS database, which is encrypted and protected with a secure access key to ensure confidentiality and data integrity. Access to the data will be restricted to authorized research personnel only, adhering to strict data protection regulations and ethical standards.